In the heart of London in the late 1950s, a new kind of establishment emerged, one that challenged the traditional coffee culture and the political foundations of its time. The Partisan Coffee House became a haven for intellectuals, artists, and activists. Part of the New Left, they sought to make sense of a world grappling with the aftermath of the Hungarian Revolution, the Suez Crisis, and growing societal commercialisation. Read more on londonski.

The Story of the Partisan Coffee House

In the late 1950s, Britain’s intellectual and cultural scene was in the midst of a transformation. A key figure in these changes was Raphael Samuel, a young Oxford graduate whose energy and boldness helped create new cultural platforms. While still a student, he joined forces with Stuart Hall, Gabriel Pearson, and Charles Taylor to found the journal Universities and Left Review (ULR). This initiative was a direct response to the tragic events of 1956 — the Soviet invasion of Hungary, which shattered many European intellectuals’ faith in the Soviet model of socialism. The publication aimed to offer a new space for reflection, where socialism could move beyond economic theory and intertwine political thought with art, culture, and daily life.

The success of ULR inspired Raphael Samuel to embark on a more practical experiment. In 1958, he founded the Partisan Coffee House, a place designed to be more than just a café; it was intended as a hub for meetings, discussions, and cultural events. The name itself was a tribute to the anti-Nazi resistance, and the concept was modelled on the legendary Parisian cafés like Flore and Deux Magots, which had been crucial to the intellectual scene in post-war France. Samuel deliberately set his creation against the commercialised establishments that were springing up in London, riding the wave of Italian coffee culture.

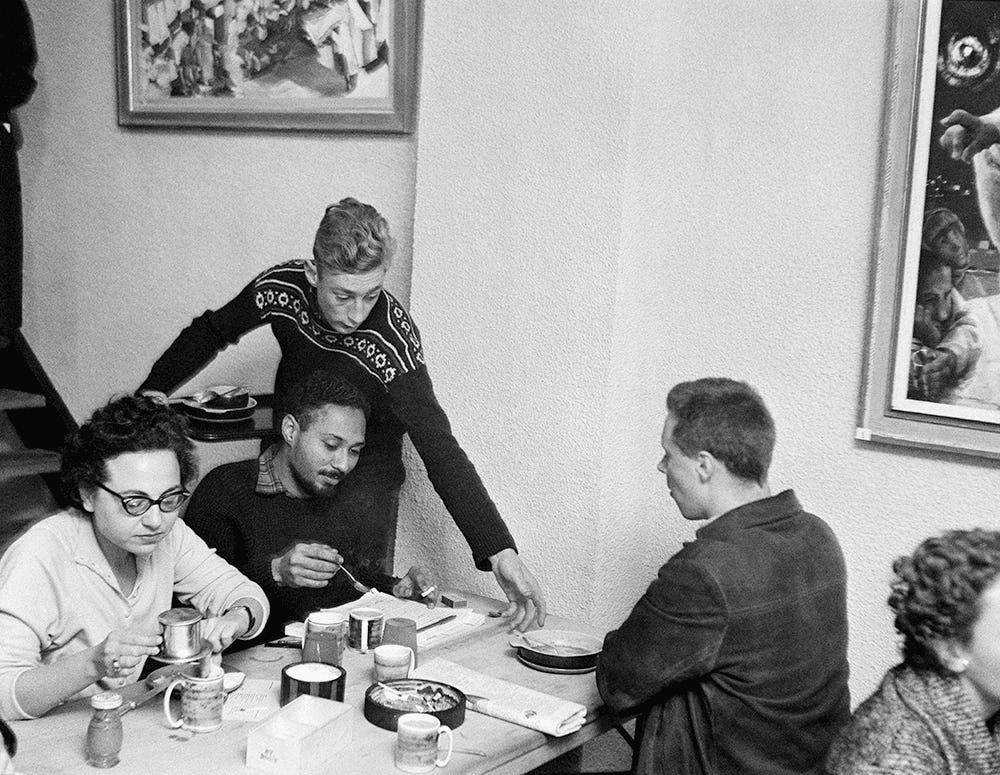

Acquiring a building in Soho, Raphael Samuel transformed it into the multifunctional Partisan Coffee House. The ground floor housed a modernist-style café, complete with unique furniture and art. The basement was a lively space for chess games, theatre productions, and music nights featuring jazz, blues, and skiffle. Despite lacking business experience, Samuel proved himself a charismatic organiser, capable of convincing others of his ideas and mobilising resources.

At the Partisan Coffee House, Samuel offered a menu that defied the prevailing norms. Instead of the typical British fare shaped by post-war rationing, he served up exotic and cosmopolitan dishes aimed at opening visitors’ minds to new flavours. Some dishes were even considered inedible, but they remained affordable and captivated those yearning for change. In this ‘anti-espresso’ café, patrons were served ‘Partisan coffee’ — a filtered brew that was more of an idea than a culinary delight. Stuart Hall later admitted that its taste was far from appealing.

Yet, practicality was the café’s Achilles’ heel. Behind the sophisticated design and artistic atmosphere lay a chaotic organisation. Cleaning was neglected, staff were often unkempt, and the financial strategy was, at best, a pipe dream. The establishment never turned a profit. Five years later, idealism gave way to reality. In 1962, the café closed its doors, the building was sold, and the debts were paid off.

Recognition and Legacy of the Partisan Coffee House

Established as a ‘socialist café’, the Partisan Coffee House stood against commercialisation and sought to offer an alternative to the post-war British climate. Within its walls, film screenings, poetry readings, and informal concerts combined intellectual pursuits with cultural creativity. The basement was a gathering spot for musicians and poets, while the upstairs library became an arena for fierce debates and conversations. Notable visitors included such 20th-century figures as Stuart Hall, Raymond Williams, Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson, and John Berger. Ultimately, the very commitment to hospitality and anti-commercialism became the cause of its downfall.